Sri Aurobindo not just mobilised the nation towards freedom through his electrifying words, but also created secret societies that would overthrow the British

As he launched Sri Aurobindo’s sesquicentennial celebrations, Prime Minister Narendra Modi movingly referred to two defining dimensions of Sri Aurobindo’s life and legacy. He spoke of Sri Aurobindo’s vision of ‘revolution’ and of ‘evolution’, it was, as the colloquial expression goes, Sri Aurobindo’s life described in a ‘nut-shell.’

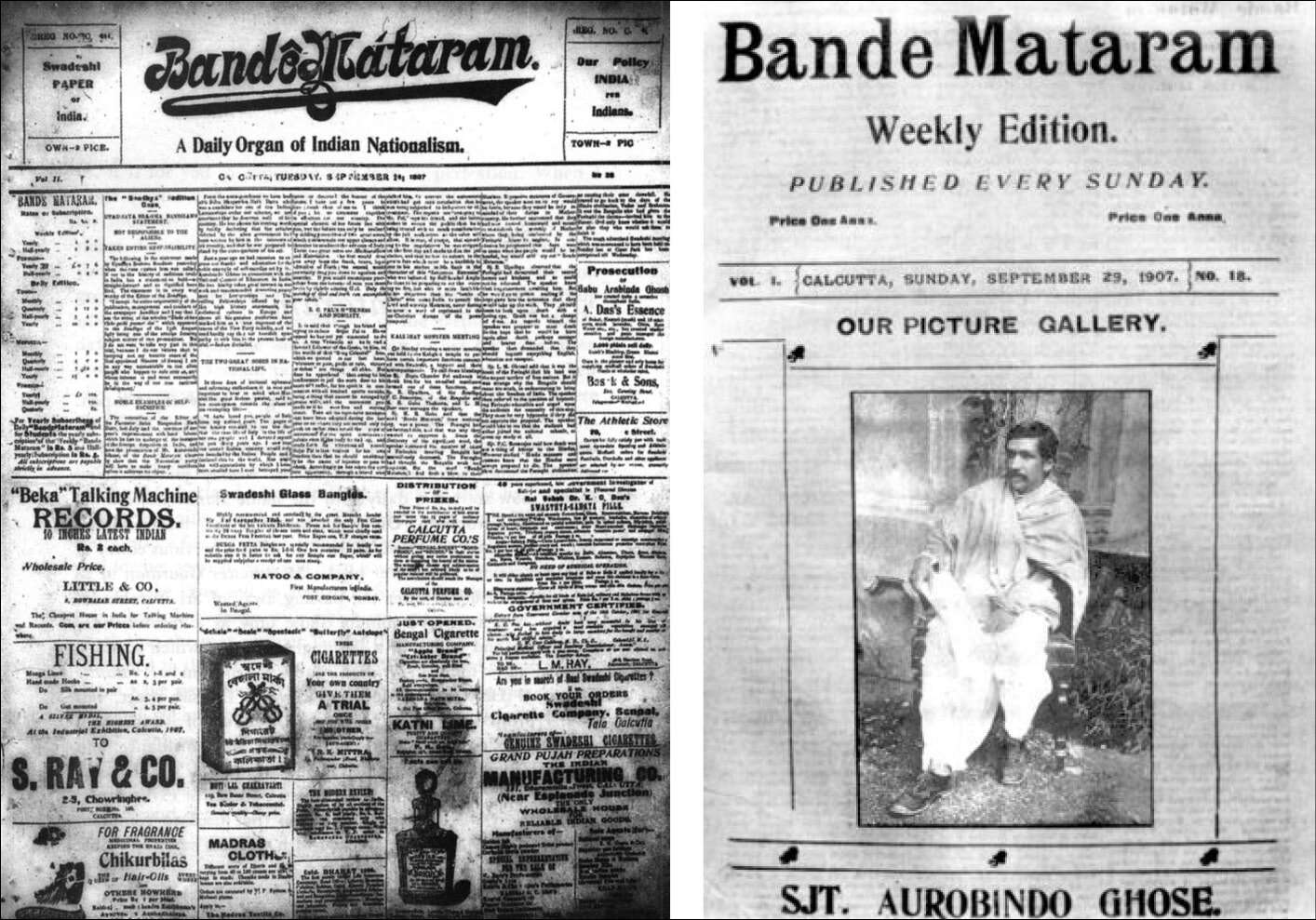

In revolution, as a revolutionary and as the leader of the revolutionary nationalists, Sri Aurobindo’s political stance and action was indeed revolutionary. It was in the pages of his uncompromisingly nationalist English daily Bande Mataram, that young India, an India in search of a galvanising political direction, read for the first time the electrifying lines demanding complete and undiluted freedom. None before Sri Aurobindo had unequivocally articulated that demand. Written during the zenith of the Empire, Sri Aurobindo’s editorials and columns in the Bande Mataram were deftly expressed, cogently and forcefully argued and breathed defiance. The political formulations of Bande Mataram, in a sense, laid the ideational and political foundations of India’s struggle for freedom for later years.

Bipin Chandra Pal, Sri Aurobindo’s colleague in revolution, perhaps gives us the best description of Sri Aurobindo as a journalist, editor and political ideologue. Of Bande Mataram, Pal writes, ‘The hand of the master was in it, from the very beginning. Its bold attitude, its vigorous thinking, its clear ideas, its chaste and powerful diction, its scorching sarcasm and refined witticism, were unsurpassed by any journal in the country, either Indian or Anglo-Indian. It at once raised the tone of every Bengali paper, and compelled the admiration of even hostile Anglo-Indian editors. Morning after morning, not only in Calcutta but the educated community almost in every part of the country, eagerly awaited its vigorous pronouncements on the stirring questions of the day…It was a force in the country which none dared to ignore, however much they might fear and hate it, and Aravinda was the leading spirit, the central figure, in the new journal…’

Bande Mataram had dynamised young India turning Sri Aurobindo into an icon among Indian youth of that era. So intense was his presence and effect, that years later, the Shankaracharya of one of the sacred Mathas, who had, in his youth, seen and heard Sri Aurobindo as the leader of the avant-garde nationalists, recalled in a public meeting in Kolkata, how in their younger days, they, followers of Bal Gangadhar Tilak, were intensely devoted to Sri Aurobindo, “You can gauge the depth of our devotion to Sri Aurobindo from one example. We used to read the Gita regularly. In the Srimad bhagavat Gita wherever there was the phrase ‘Thus spake God’

[Sri Bhagavanuvacha], we replaced it with ‘Thus spake Aurobindo’ [Sri Aravindauvacha]. That was how we saw Sri Aurobindo.” The young and iconic ‘Bagha Jatin’, Jatindra Nath Mukherjee, acknowledged by Sri Aurobindo to have been his ‘right hand man’, one of the most youthful icons in the saga of India’s struggle for freedom, took up Sri Aurobindo’s line of armed resistance to overthrow British rule, pursuing it till his martyrdom in the ‘Battle of Balasore.’

So deeply embedded was Sri Aurobindo’s influence in the youth of his era, that even decades later, they could still feel his aura and connect to him as their leader. In preparation to the launching of the Indian National Army (INA) in September 1942, revolutionary Rashbehari Bose, who had been deeply influenced by Sri Aurobindo as a youthful revolutionary in Chandernagore, issued a public appeal from Tokyo, in March 1942, saluting Sri Aurobindo ‘to whose inspiring call we owe the birth of positive Indian nationalism. Sri Aurobindo is the foremost of those seers of Indian nationalism…due to whose burning speech and thundering pen, patriotism came to have a fresh and profound meaning for modern Indians. To him this salute is offered…This salute is offered to him in the time-honoured Indian custom of asking for the blessings of the elders and pioneers before undertaking a great and noble task. May he be pleased with my fresh determination to do my bit in the cause of making India of the Indians and Asia of the Asiatics. I salute you Sri Aurobindo.’

1907 — the year which saw Sri Aurobindo churn out the maximum number of articles and columns in Bande Mataram as a political leader, ideologue and philosopher — was also the 50th year of the first war of independence of 1857. The Indian psyche was in ferment. The partition of Bengal had just been announced and effectuated by Curzon, intense indignation had seen protest waves sweep the country, Sri Aurobindo, on leave from Baroda, saw the episode, as he told the British journalist and author with sympathies for the Indian nationalists, Henry Nevinson, as ‘the greatest blessings that had ever happened to India’, since, ‘no other measure could have stirred national feeling so deeply or roused it so suddenly from the lethargy of previous years.’ He sought to channelize the emotions and forces unleashed by the partition of Bengal through a concrete political programme and action towards a distinctly articulated goal.

To the struggle for freedom, to its early aspirations, Sri Aurobindo imparted two directions, one was the public political action, the other was the building and sustaining of networks of secret societies which would work to violently overthrow British rule. ‘The choice by a subject nation of the means it will use for vindicating its liberty, is best determined by the circumstances of its servitude. The present circumstances in India seem to point to passive resistance as our most natural and suitable weapon. We would not for a moment be understood to base this conclusion upon any condemnation of other methods as in all circumstances criminal and unjustifiable.’ This in itself was a revolutionary formulation made publicly at a time when most political leaders followed a timid policy of mendicancy driven by the spirit of supplication and of appeal to the colonial masters as the only legitimate approach to the demand for freedom or autonomy.

Long before ‘purna Swaraj’ and ‘non-cooperation’ were to become the declared line of political action and demand by the Congress, Sri Aurobindo as the leader of the ‘new group, the ‘new party’, had made the demand and had extensively examined these in the Indian political context. ‘Political freedom is the life-breath of a nation, to attempt social reform, educational reform, industrial expansion, the moral improvement of the race without aiming first and foremost at political freedom, is the very height of ignorance and futility…The primary requisite for national progress, national reform, is the free habit of free and healthy national thought and action which is impossible in a state of servitude.’

In his insistence on aiming at not only ‘a national Government responsible to the people but a free national Government unhampered even in the last degree by foreign control’, Sri Aurobindo came across as revolutionary in his direction to the revolution. None before him had articulated it thus in words of steel. This brought to the movement the youth who, having read and heard him, abandoned property, pedigree, estate and career to plunge into the struggle to liberate India.

This is a phase worth revisiting on the occasion of Sri Aurobindo’s 150th birth anniversary celebrations and the 75th years of Swaraj.

(The writer is a member of National Executive Committee (NEC), BJP, and the Hony. Director of Dr Syama Prasad Mookerjee Research Foundation. Views expressed are personal)